Guan Yang | May 13, 2022

The Titles Edition

On Italian, diction, and subtitles

Recommended Products

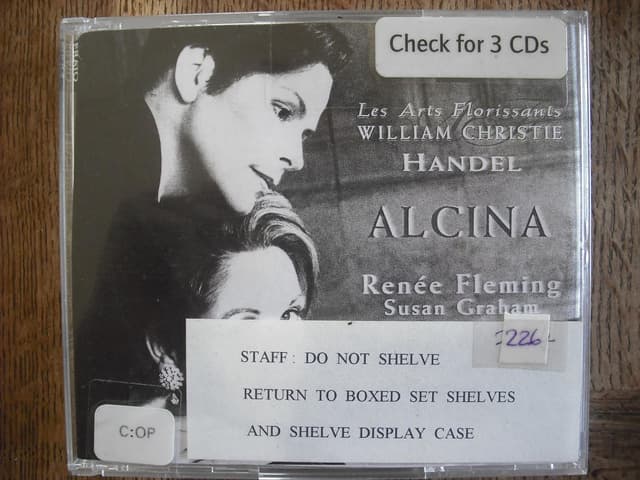

Handel’s best opera, premiered in 1735 featuring the famous aria 'Tornami a vagheggiar'.

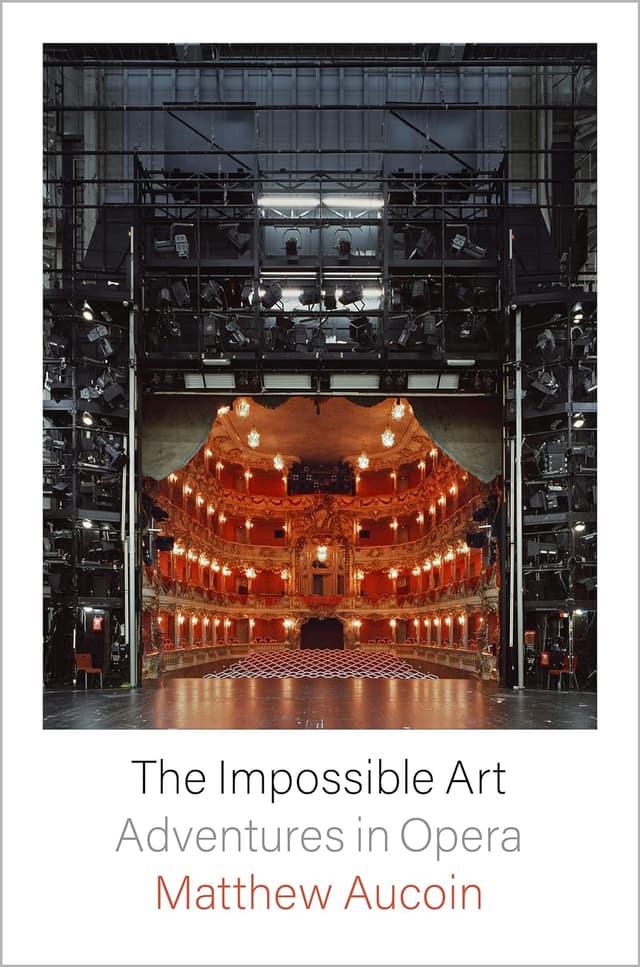

In his book, composer Matthew Aucoin describes opera as 'an imagined union of all the human senses and all art forms—music, drama, dance, poetry, painting.'

A 2020 opera by Matthew Aucoin with each sung line projected into the set, offering complete control over what the audience sees, hears, and reads.

Guan here. Italian-language opera first appeared in London in 1705 with Jacob Greber’s Gli amori d’Ergasto. Although productions continued for another two hundred years, the era peaked in the 1720s and 1730s, when the preeminent composer was the Saxon-born naturalized Brit George Frideric Handel, who wrote 39 Italian operas for the London stage between 1711 and 1741.

Italian was not widely spoken in London at the time, so how did anyone understand the words? Well, like opera audiences today, many didn’t. Given the often convoluted plots and formulaic arias, they might have rightly preferred to just sit back and enjoy the music.

Londoners did have a secret weapon unavailable to modern opera-goers: the house lights stayed on throughout the show, and a shilling bought you a printed libretto of the entire opera with a facing translation. (The price of an orchestra ticket was 5 shillings.) Here’s the ending of Act 1 from Alcina (1735), Handel’s best opera, with the famous aria “Tornami a vagheggiar”:

This scan is from the Handel collection at the Foundling Museum. Printed libretti are an important source for 18th-century opera, as many more of them survive than musical scores. The Library of Congress has 12,000 pre-1800 libretti; Claudio Sartori’s catalog lists 25,000 editions.

At a modern opera house, darkness descends upon the audience when the performance begins. A printed libretto is no longer available, and I can report that reading along on your phone is not well received. Instead, titles are projected or displayed above the stage. And although diction has improved over the years, opera can be hard to understand even in a language you know, so houses in Italy tend to have Italian surtitles (above the stage) even for Italian-language works. The fancy folks at the Metropolitan Opera of New York display subtitles on a small vacuum fluorescent display in front of each seat.

Why is this interesting?

The Italian opera craze in 18th-century London anticipated the popularity of culture presented in a foreign language, while we read along with a translated text. And perhaps also a time when we’re constantly reading, consuming text non-stop, whether it’s newsletters, doom-scrolling, at the opera, or while watching television.

Opera-goers and those living in countries where dubbing is rare have long been accustomed to translated titles (as well as those who use same-language captioning for accessibility). More audiences are now joining them, especially thanks to Netflix’s global strategy. The Economist has declared Netflix to be creating a common European culture, one subtitled series at a time. Other streamers have joined the bandwagon: the 2018 television adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend is HBO’s first foreign-language production. (The third season recently ended, and it’s great.)

Stavroula Sokoli: “Subtitling Norms in Greece and Spain,” in Audiovisual Translation: Language Transfer on Screen

Viewers of global Netflix series such as Squid Game turn on subtitles in such large numbers, even in traditional dubbing countries, that reading text is now part of the default experience of these works. The quality of the translation, how literal or free it is, whether every line of dialogue is translated or some are omitted, how the titles appear on screen, and the global translator shortage are no longer niche concerns of a few viewers in Northern Europe. And indeed, the Squid Game subtitles have sparked plenty of takes.

In his book The Impossible Art, composer Matthew Aucoin describes opera as “an imagined union of all the human senses and all art forms—music, drama, dance, poetry, painting.” Aucoin forgot to add text to that list, but he embraced the centrality of reading in opera with Eurydice (2020), which has each sung line projected into the set, affording Aucoin and stage director Mary Zimmerman complete control over what their audience sees, hears and reads:

Still from the 2021 Metropolitan Opera production

Japanese anime producers have long had approval over their subtitle scripts. Creators of newer multilingual shows such as Acapulco, Tehran, and ZeroZeroZero have translation and subtitles (or the omission of subtitles) in mind from the beginning:

Gina Gardini, executive producer of “ZeroZeroZero,” says she and her team made a conscious effort to open the pilot with an English-language voiceover before diving into Mexico and Italy, where Spanish and Italian are, respectively, spoken with English-language subtitles. … Gardini and her team took great pains to make sure subtitles reflected the original language and weren’t overly obtrusive.

Translations and titles are increasingly considered integral to the work and approached with creativity and purpose. In this new golden age of multilingual and cross-cultural entertainment, there’s no escaping text. (GY)

Quick Links:

On the translation of the title of Elena Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter by Ann Goldstein. (GY)

Joyce DiDonato on performing Handel’s arias. (GY)

China’s subtitling communities; the loss of YouTube community captions. (GY)

The unbelievably batshit British dubbing process for a 1976 Japanese production of the Chinese classic The Water Margin. (GY)

--

WITI x McKinsey:

An ongoing partnership where we highlight interesting McKinsey research, writing, and data.

Social media as a service differentiator: How to win. Let’s say you have a question about a product or some feedback for the company about your experience with it. Chances are you’ll head to social media. Customer service is a public affair, and more companies are turning to social as a full-service channel that can help customers and drive positive brand experiences. A new article lays out a framework on six key areas of social media servicing excellence.

–-

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!).