Matt Locke | October 2, 2025

The Theatre Europe Edition

On nuclear war games, escalation, and making the call.

Matt Locke (ML) is a WITI contributor and the Director of Storythings, a content agency based in the UK. His previous WITIs include the Andy Warhol Album Covers Edition, the TV Schedule Edition, and the Photobooth Edition.

Matt here. Back in the mid-1980s, my teenage life was dominated by two things: Early 8-bit computers, and the likelihood of all-out nuclear war. It’s strange to recall how present the risk of nuclear war was in our daily lives. My family had conversations about what we’d do if the four minute warning went off, and whether we could get back home in time to be together as the bombs fell.

So when Theatre Europe came out in 1985, it triggered both my passion for computer games and the queasy dread of my most existential fear. This was a period when imagining the unimaginable - a nuclear holocaust - was a recurring cultural theme. The War Game, a 1966 film about the impact of nuclear war in the UK, had finally been aired, after being held back by the BBC for twenty years for being “too horrifying for the medium of broadcasting”. Raymond Briggs’ harrowing graphic novel When The Wind Blows was released a few years earlier, and would come out as an animation in 1986. In the US, The Day After was released in 1983, the same year that Matthew Broderick inadvertently took the world to the brink of nuclear disaster in War Games.

Why is this interesting?

A recurring theme of mid ‘80s nuclear war culture was the risk of escalation, and how impossible it would be to stop escalation leading to a nuclear holocaust. Films and books either told the stories of ordinary people failing to deal with the horrific aftermath of a nuclear war, or of how NATO and the Soviets would fail to halt the process of escalation once it had started. There were no protagonists in nuclear war stories, just the failure of people to stop or cope with the events happening to them. Only War Games had a protagonist who could stop a nuclear war, but I didn’t hold out much hope that teaching a computer tic-tac-toe would really save humanity.

Theatre Europe was the one rare opportunity to have some agency in these stories. The game starts by offering you the choice of playing either as NATO or the Warsaw Pact, and through a turn based battle mechanic you’d move your ground and air forces, deciding when and who to attack. The game is ‘won’ either when the Warsaw Pact crosses the Rhine to reach Bonn, or when the NATO forces inflict heavy enough casualties to force the Warsaw Pact to surrender.

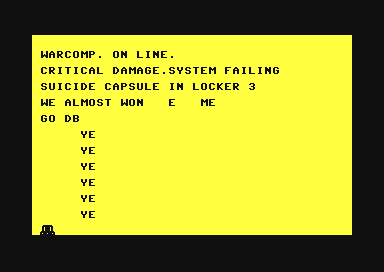

But the game also had a ‘special mission’ screen, offering the player the ability to use chemical or nuclear weapons. This is where the game introduces the potential for escalation, with the option of initiating a first strike, or having a ‘reflex’ mode, where you launch weapons immediately in response to your opponents’ first strike. Using the special missions inevitably led to escalation - chemical weapon attacks led to tactical nuclear strikes, which led to reflex attacks in response, and ultimately the existential horror of global thermonuclear war.

The game designers introduced a remarkable mechanic for these special missions. To order a special mission, the player had to first call a real phone number to get a code word (MIDNIGHT SUN) that unlocked the chemical and nuclear options. The pre-recorded message at the other end of the call gave you the code word over a horrifying audio montage of crying babies and other sounds evoking a post-nuclear holocaust. In giving you agency, the game also forced you to consider the consequences of your decisions.

I remember playing the game with friends, and how our mood changed the first time we made that call. The game had triggered some tabloid controversy, with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament accusing its designers of ‘bad taste’. Those critics had clearly never actually played the game. Far from being exploitative of cold war paranoia, making that call gave you a chilling and visceral sense of the weight of the decision to use nuclear weapons; to start the escalation that would lead to our worst, most existential, nightmares.

Forty years after that game, and eighty years after the uses of nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the horrors of nuclear war feel more distant and abstract, even with the blockbuster success of Oppenheimer and the threats of ‘tactical’ nuclear strikes in Ukraine and the Middle East. Maybe there are too many other existential risks now, but it feels time for a new piece of culture to remind us of the visceral horror of nuclear war, and the grim inevitability of escalation once the decision to use the weapons has been made. Theatre Europe, using only an early 8-bit computer game and a phone call, taught me that there is no such thing as a tactical nuclear weapon, no outcome from a first strike that doesn’t lead to a nuclear holocaust. We could use another reminder of that today.

Quick Links

I played Theatre Europe on an Amstrad 464, but the best description of the game is on this Commodore 64 Wiki

This YouTube playthrough of the game gives a sense of the gameplay (including the very skippable arcade screens), but sadly not the experience of making that phone call.

This scan of a profile of PSS, the game’s publishers, from a 1986 edition of Your Computer gives a bit more background on the controversy the game generated, but also the detailed research the designers carried out in developing it, including remarkable data from the Soviets.

(ML)