Unknown Author | January 29, 2026

The Seydou Keïta Edition

On style, portraiture, and self-determination.

Colin here. Seydou Keïta ran a portrait studio in Bamako, Mali from the late 1940s through to the country’s independence. He might not be a household name, but you’ve seen his influence everywhere—from Tyler Mitchell’s Vogue covers to the way fashion editorials now treat patterns as protagonists.

Keïta worked during a moment when West Africa was defining itself after decades of colonial rule. His studio, just off the railway station in the commercial district, became something more than a place to get a picture taken—it was a space for people to perform the versions of themselves they were still becoming.

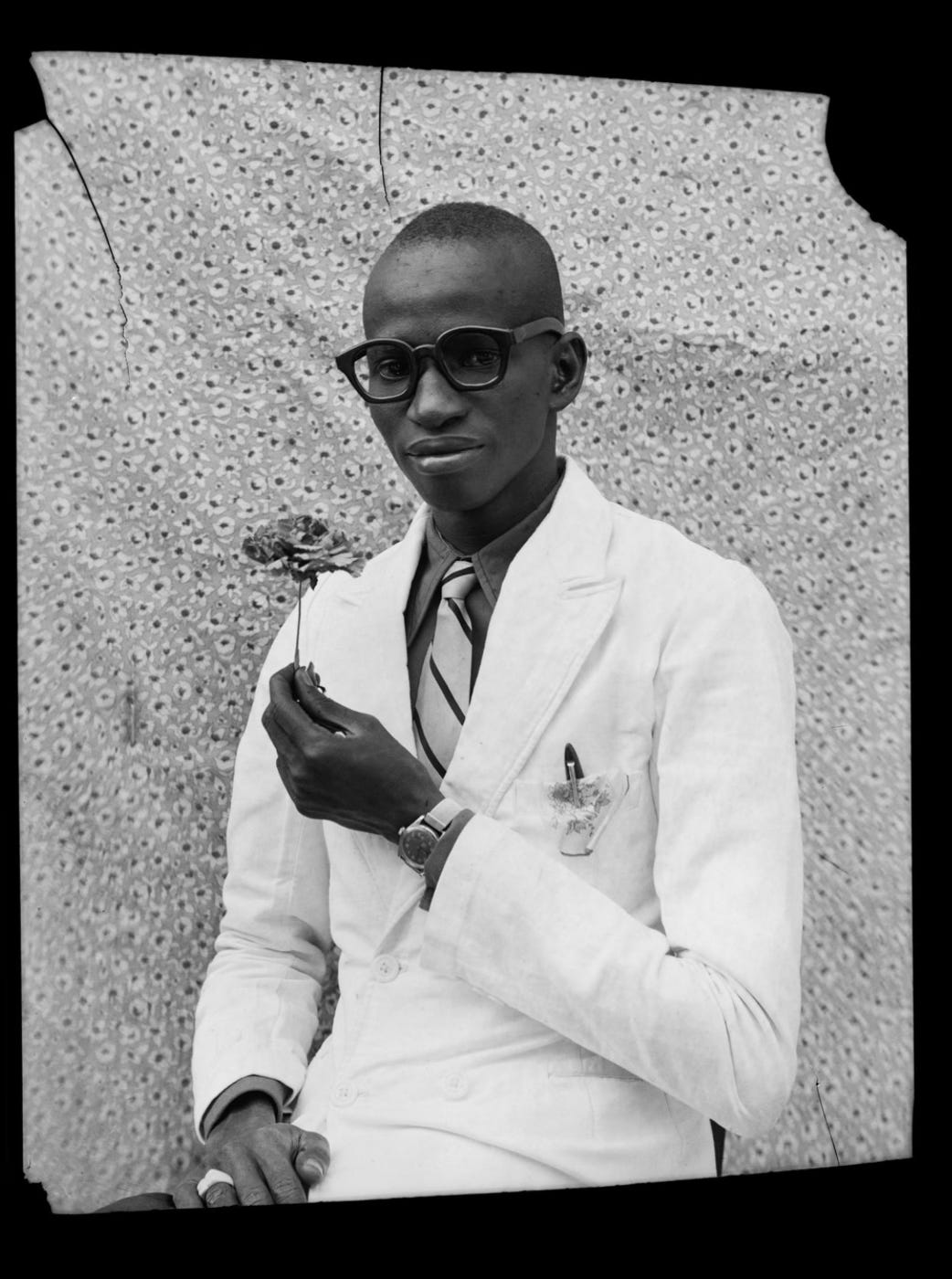

The process was collaborative in ways that most portraiture isn’t. Keita kept a trunk of prints that caught his eye, and his sitters chose from that ever-growing wardrobe of patterned fabrics. They also selected props: a scooter, a radio, a fountain pen, a briefcase. Then came the iteration and negotiation: how to sit, where to look, what pose best captured the person they wanted to be. Finally, Keïta arranged it all with the expertise of a skilled editor or couturier—adjusting a collar, tilting a chin, positioning hands.

In the resulting images you see a wide, delightful range: confidence, swagger, tenderness, ambition. Everyday people who look like royalty, jazz musicians, and sometimes all three at once. A young woman in a floral blouse against a geometric backdrop, chin raised, gaze direct. A man in a double-breasted suit holding a cigarette like it’s a scepter. All deliberate acts of self-construction.

After independence, his negatives were boxed up and nearly lost—until the 1990s, when the global art world finally noticed. Today he hangs in MoMA, the Pompidou, and most recently, the Brooklyn Museum.

Why is this interesting?

Keïta’s portraits show how cultural power often emerges from the edge, not the center. A Bamako studio—without the hype, capital, and public relations frenzy we see around art and photography today—ended up shaping contemporary portraiture from Lagos to Los Angeles.

And there’s a broader point: style is self-determination. His sitters used photography to claim their place (and swagger) in a world that was rapidly reorganizing. Long before “African photography” became a global art-market category, Keïta was showing the world how Africans saw themselves.

A strong point of view—on both sides of the camera—mattered more than technology or hype. That’s why the images endure. (CN)