Michael Grant | October 14, 2021

The Poptimism Edition

On bias, Daft Punk, and pop hits

Recommended Products

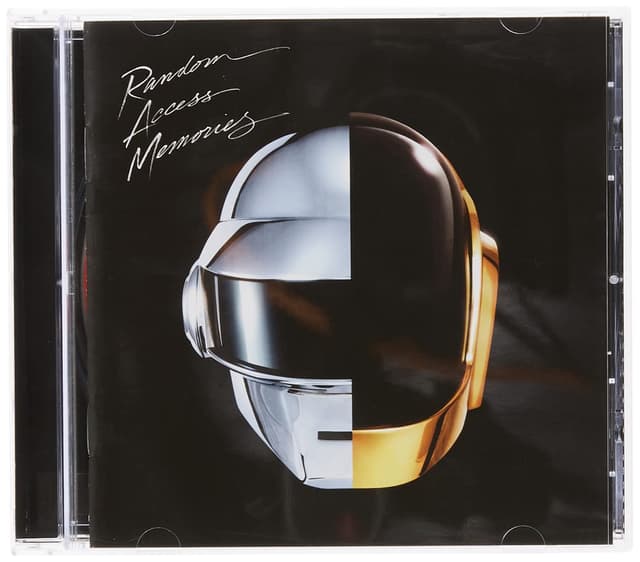

An album by the electronic duo Daft Punk, initially questioned for its quality, but part of the discourse on Pitchfork's re-scoring of albums.

A single by My Chemical Romance that was highlighted as a masterpiece in the context of Poptimism.

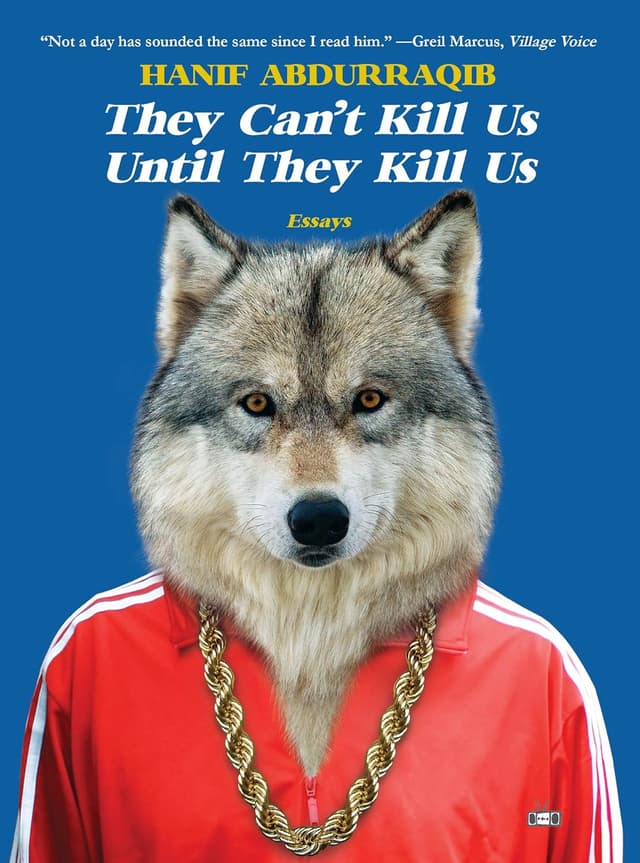

A book featuring essays on music that engages with Poptimism and the new scope of music criticism.

Michael Grant (MG) is a writer, creative director, and connoisseur of spicy music takes. He was a Warriors fan before you were. Michael’s music takes are exclusively his and do not necessarily represent the tastes of your regular WITI editors - Noah (NRB)

Michael here. Last week, the formerly tastemaking music site Pitchfork published “Rescored,” a list of do-overs for album rankings. While not as hilariously self-serious as the time they spent a week reviewing the entire Beatles catalogue (spoiler: turns out the Beatles were very good!), this recent re-scoring exercise is an equally good example of Pitchfork’s reverence for their own rightness.

But they are certainly right about initially being wrong about one album in particular: the bad album Random Access Memories by the good electronic duo Daft Punk. Coincidentally, in a recent Discord discussion, I called Daft Punk one of the three most overrated artists of my lifetime. This (correct!) opinion was, apparently, an act of cultural treason amongst coastal elite dads, enough to rouse Noah (NRB himself) from his speed-cubing den. He disagreed. Daft Punk were hugely important and influential, he said, having released two classics out of the gates. I argued that is why they were overrated, because they had in fact not released good music since 2001, even as their stature and coverage grew exponentially leading up to the release of R.A.M. in 2013, and carrying forward another half decade beyond that.

Noah theorized that maybe the overexposure/overrating of Random Access Memories was due to a weird point in time when indie-type things crossed over semi-permanently into the mainstream. Maybe they just got swept up in a shift in the discourse? I said well, yeah, that was around when Poptimism began to really take hold. Noah said, “What’s Poptimism?”

Why is this interesting?

Despite having a silly name, Poptimism changed the way music is covered. Full stop. While few people living outside the music-criticism cul-de-sac have heard of it, this mini-movement gained steam through the years and, I believe, is largely responsible for what gets covered today, and how. Without sending you to too many articles from years past, the easiest way to define the idea of Poptimism is what it was intended to stand against and correct for: Rockism. You can guess what Rockism is. The old canon. The fossilized record of the music that we were told mattered in the second half of the 20th century. You might guess the bands who were deemed the most important—treated the most as artists rather than mere entertainers—were mostly in a lineage of White Dudes Making a Point.

So Poptimism came along to point out that hey, you know, by focusing so much energy on the genius of Van Morrison, the Velvet Underground, the Stooges, and on (and on) all the way through Neutral Milk Hotel, maybe just maaaybe there were other genius-level talents being largely ignored in terms of “serious” criticism. Namely: everyone on the pop charts, the R&B charts, anything mainstream. What if all that stuff was treated as if it mattered?

Well suddenly you would greatly expand the scope of what merits coverage in serious music criticism, right?

The first time I remember hearing about Poptimism was all the way back in 2006, when (the wonderful!) Maura Johnston was still writing for Idolator. She treated My Chemical Romance’s newly released single “Welcome to the Black Parade” as the masterpiece it was, and still is. At the time I would have otherwise written it off as mainstream emo (audible scoff!). But I gave it a try, and, whoa. One of the best rock songs in years—and one I would never have taken seriously unless a serious mind told me to do so. That’s the idea, writ large. “These things previously deemed unserious are in many cases equally or more seriously excellent than the established seriously excellent things.”

Where the gold standards of music-as-art were previously reduced largely to Bob Dylan, proto-punk, punk, and post-punk, Poptimism emboldened (prodded? guilted?) critics to use their same analytical and expressive toolsets to address, say, a #1 selling mainstream R&B release. Crucially, it also led to many new writers publishing good takes about music that were unbeholden to the old canon (of music, and of critics).

After all, Pitchfork reviews Taylor Swift albums now. It seems silly they didn’t always, but here we are. You’d be right to assume this will continue to inform the retrospective canon as well. Look at Rolling Stone’s recent revised lists of the top 500 albums and songs of all time. The top 20s look very different than they would have even five or ten years ago.

This is all good. And necessary. The word inclusive comes to mind. Even Enya and Sade have rightfully been bumped up to the critical top tier (though Enya has been doing just fine living in her literal castle for a while now). The first Luther Vandross album is on lists right next to the Beatles and Neil Young. It is (probably) only a matter of time before George Michael’s Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1 is at last enshrined as a 90s masterwork!

But I think what’s interesting goes beyond what was won in the Poptimism vs Rockism discourse wars of the aughts. There’s, of course, also the question of what was lost. And I’m not talking about the undeniable lack of scorched-earth assholery these days. It certainly feels like music reviews today are wielded as correctives in a fight that’s already over. Look how much we like this album our publication wouldn’t have liked before. Or more performatively, look how little we like this album our publication would’ve previously hailed.

Combine the firmly entrenched Poptimism paradigm (mostly good!) with the rise of online stan armies (mostly terrifying!) and we’ve got a situation where it’s hard to gauge to what extent music criticism is even about, like, the music anymore. If you say a popular thing is lightweight, you risk looking retrograde. If you go harder and say a popular thing straight up sucks, you risk having an Extremely Online fan army make your life miserable. And all the while, constantly evolving and often ephemeral trends in the discourse might be influencing music reviews and coverage more than the songs in question.

But at least our ratings-obsessed tastemakers, after achieving heretofore untold levels of critical clarity regarding the lesser works of Daft Punk, can presumably stalk unburdened toward the Final Boss of being overrated: Beck. (MG)

Quick Links:

What Actually Draws Sports Fans to Games? It's Not Star Athletes. [Thx SV4] (NRB)

What Really Happened at the 2021 DC Peaks 50 Mile Race? (NRB)

__

WITI x McKinsey:

An ongoing partnership where we highlight interesting McKinsey research, writing, and data.

The EX factor. If you're not paying attention to employee experience, or EX, you should—particularly in this era of workplace upheaval and high attrition. Companies that focus on it can strengthen employee purpose, ignite energy, and elevate organization-wide performance. A systematic approach can help; here's how.

__

Thanks for reading,

Noah (NRB) & Colin (CJN) & Michael (MG)

—

Why is this interesting? is a daily email from Noah Brier & Colin Nagy (and friends!) about interesting things. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing.