Jason Boog | May 1, 2025

The I Ching Edition

On ancient texts, meaning, and change.

Jason Boog (JB) leads editorial at Fable, a social reading platform for book clubs. He is also the author of The Deep End: The Literary Scene in the Great Depression and Today and contributor of The Euchre Edition and The ECM Sound Edition for WITI.

Jason here. Sometimes when the first page of a new writing project feels especially blank, I pull out my copy of the Chinese masterpiece, the I Ching. To use this 3,000-year-old “Book of Changes,” I shake three pennies in my cupped hands and spill them on the table six times. Then I use this chart to convert the results of those coin tosses into six different lines, which I stack into a “hexagram.” The main text of the I Ching contains 64 of these hexagrams, each accompanied by layers of aphoristic analysis composed by different writers over three millennia. I like my coin-toss method, but people use dice, cards, and yarrow stalks to generate hexagrams as well.

Before starting this WITI newsletter, I threw Hexagram 28 with my pennies. According to my battered copy of Total I Ching by Stephen Karcher, this hexagram translates to “Great Traverses.” Every hexagram includes its own “Judgment,” or a new way to look at a question, situation, or problem. Karcher always makes me feel like I’m in middle of some hero’s journey, and his translation of Hexagram 28’s judgement does not disappoint: “A crisis; gather all your strength; hold on to your ideals; breaking the rules, becoming an individual; the great transition, major site of transformation; a seed figure.”

I carried those dramatic images and ideas with me for the rest of the week, seeding my notebooks with thoughts about the ideals that brought me to the I Ching many years ago. “A writer’s mind swirls with trivia, images, and a torrent of story ideas,” wrote Jessica Page Morrell in The Writer’s I Ching, a book published before social media and smartphones had permanently damaged my ability to focus. “The sheer volume of all these images and data can obscure the solution. The I Ching creates the bridge that provides the single answer when you most need it.” Suddenly, my WITI essay wasn’t a stack of disorganized research anymore—I was making a great traverse and finding my way to someplace new.

Why is this interesting?

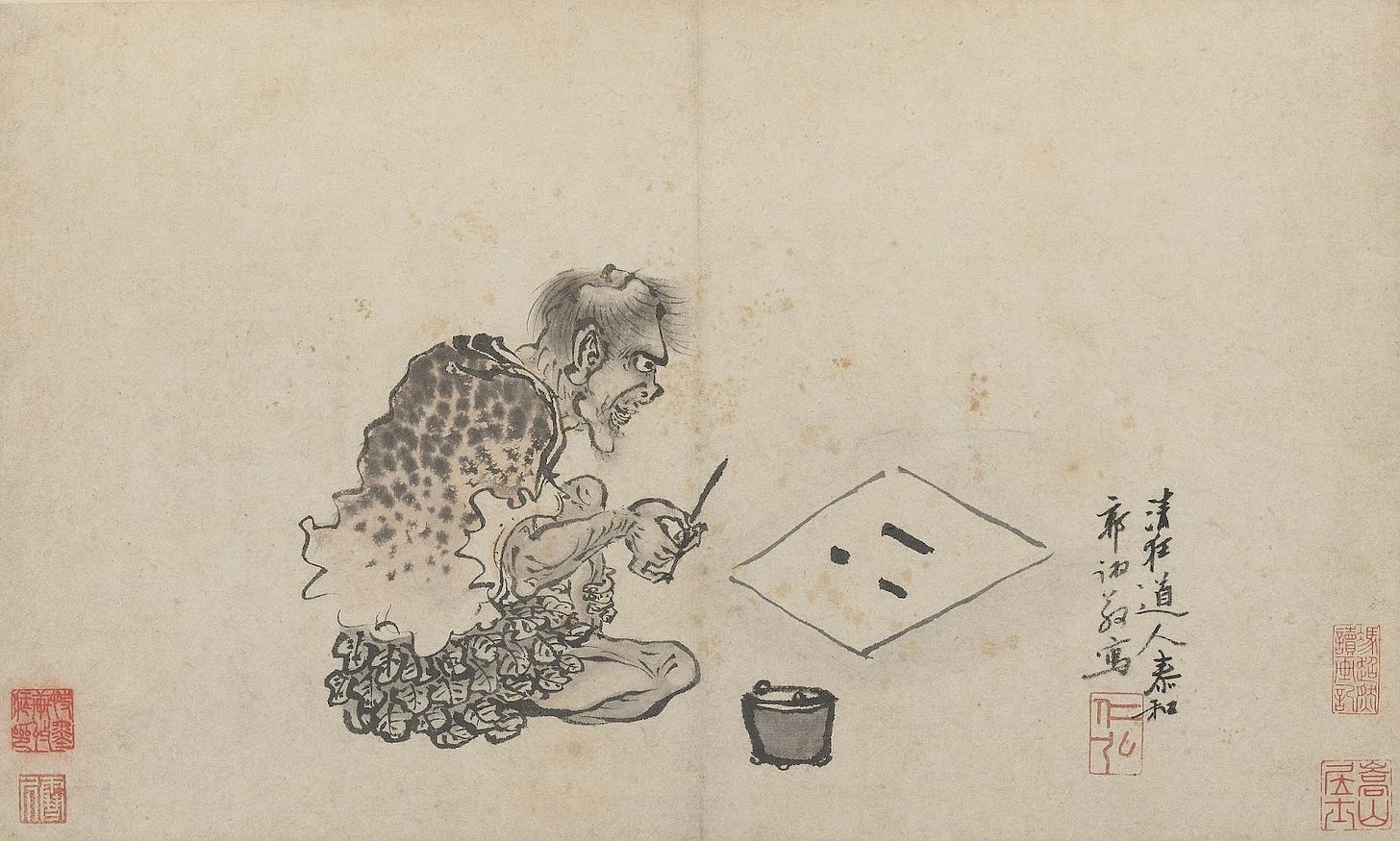

The origins of the I Ching are literally mythical, attributed to a Chinese ruler named Fu Xi. This divine emperor is said to have created eight trigrams, each with its own unique balance of the yin and yang forces that flow beneath the universe: Earth, Fire, Heaven, Lake, Mountain, Thunder, Water, and Wind. Those original eight trigrams evolved into 64 hexagrams over the centuries, as generations of authors added spiritual and philosophical commentary like geologic strata in the text, including legendary contributions attributed to King Wen of Zhou and Confucius. (I’m not even remotely qualified as a scholar of Chinese literature, so I recommend reading Eliot Weinberger’s New York Review of Books essay for an excellent introduction to the history of the I Ching.)

Western readers have sought meaning in this ancient text for centuries. Jesuit missionaries tried to give it a Christian spin in the 18th Century, scholars dissected it in the 19th Century, and generations of mystics, hippies, and New Agers argued about it throughout the 20th. Recent writers have found increasingly dubious uses for the text. There’s The I Ching of Management: An Age-Old Study for New Age Managers, The Golf Ching: Golf Guidance and Wisdom from the I Ching, and, predictably, The I Ching of the Stock Market. “Part of the book’s power is precisely that it has meant so many different things to so many different readers and commentators over the ages,” wrote John Minford in his 2015 translation. “There can never be a definitive version of the I Ching in any language. Its ‘meaning’ is simply too elusive. All interpretations and translations are works in progress.”

It’s interesting to read descriptions of the creative I Ching experience, but you can actually hear this interpretive process in Geoffrey Poole’s 3-minute song, “Follow the River.” This I Ching-guided composition opens with a series of delicate and tentative notes as a solo pianist explores the uppermost octaves of the instrument, repeating and playing with the ideas suggested by one hexagram. You can hear when the melody finds its path, a musical expression of how the I Ching connects us to the flow of the ever-changing universe — that’s “The Way,” or what the ancient Chinese philosopher Laozi called Tao.

With the pages of 2025 feeling especially blank these days, I turn to the I Ching to think about my own life as well. I don’t believe that there is some cosmic destiny charted for me in the stars, but I love reading what Minford calls the “numinous phrases” in my various translations of the I Ching. These “shards of old belief and myth” reframe my everyday uncertainty and disorganized thoughts with fragments of ancient stories. Change is always coming, whether or not I’m ready for it. There is no single correct way to proceed (in a WITI draft or life), but the I Ching illuminates my path with its numinous language. (JB)

Quick Links:

If you want to try the traditional yarrow stalk method of I Ching, you can order a bundle online. (Apparently “hand-picked in northeast China and individually groomed by hand.”)

Why yes, I do have a favorite I Ching app. It’s a simple way to try the coin method, and you can build your own digital library of I Ching translations.

Philip K. Dick was obsessed with the I Ching, and it became a part of both the story and the construction of The Man in the High Castle.