Rohan Routroy | November 4, 2025

The Hollywood Originality Edition

On consolidation, Nobody Wants This, and the human cost of second-screen viewing.

Rohan Routroy (RR) is the founder of Thirty Eight, a contemplative strategy collective advancing human flourishing through meaningful partnerships. The company will limit itself to 38 projects in its lifetime—a nod to working on finite projects with the hope of infinite impact.

Rohan here. Warner Bros. pulled off a miracle this summer with Sinners. It was the first original screenplay to cross $200 million domestically since Pixar’s Coco in 2017. Animated films have a much wider audience than a movie about vampires in the South who like to tap dance to delta blues, so that’s not really a benchmark. To find the last live action original that hit that milestone, you’d have to go all the way back to Gravity in 2013. Still one of the best opening shots in a summer blockbuster, but I digress.

Despite this miracle and a fairly successful slate of movies from Warner Bros., Netflix is reportedly eyeing their studio and streaming business.

Why is this interesting?

Where’s Lina Khan when we need her? Jokes aside, if the oligopoly pattern we’ve seen across tech, retail, and transportation comes for storytelling too, we’ll have to ask a harder question: what happens to culture when imagination itself gets consolidated?

Yes, Netflix is the studio that financed indie icon Richard Linklater’s last two films, and bought Martin Scorsese’s ignored script when no other studio would. But it’s also, after all, the same company that pioneered “second-screen viewing”—corporate jargon for keeping audiences passive, half-scrolling whatever the small screen algorithm feeds them while an episode of Nobody Wants This feeds mediocre writing on the big screen.

I am not bemoaning the business model of how these oligopolies operate; my concern is an entire cultural shift towards comfort in our consumption. I personally felt it when Tiger King became the #1 show in North America, right after that week in March 2020 when the world stopped. Rather than contemplation, we immediately went for the equivalent of a double cheeseburger with triple-fried fries. And there’s a straight line to be drawn from that to the lack of depth in most things that currently hit the mainstream, from the books we read to the movies we watch and the songs we listen to.

What we pay attention to is increasingly and systematically designed to appeal to our passivity or, in the worst cases, to our lack of thinking. We end up in a world where hubris is taken seriously, and serious issues are ignored as “too deep.”

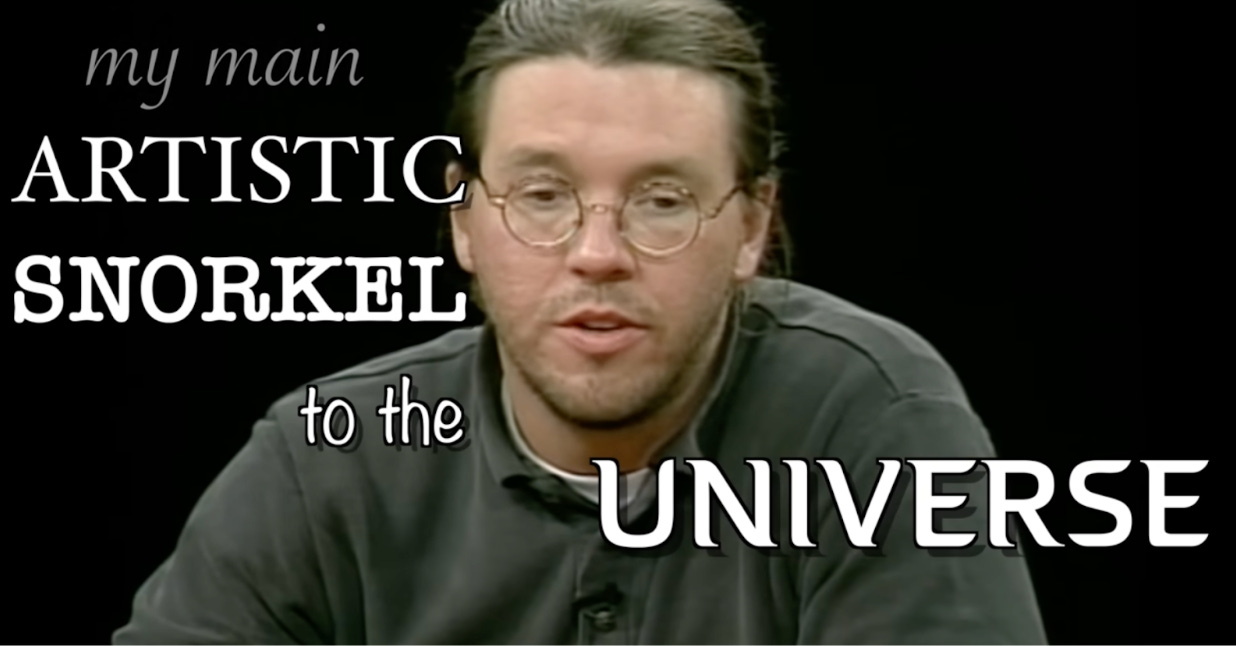

You might ask me: Why does it matter? Shouldn’t people just watch what they want to watch, whether it’s Ryan Coogler’s latest or Love Is Blind? To that, I have to quote the man who sent us a warning long before the influence of algorithms on our subconscious: David Foster Wallace.

In an interview with Charlie Rose, he described television as his “main artistic snorkel to the universe.” This is critical: Our greatest artists are always reacting to and learning from the other culture they consume. In the best cases, those artists produce work that helps us understand each other more, as well as the time period we’re living in.

Now imagine Wallace’s snorkel running through the current algorithmic heap of comfort content, sustained by a business model that can’t justify appealing to the higher selves within us. What would our artist breathe in? What kinds of stories would they be inspired to tell and to whom?

A fair example here would be Chloé Zhao. After making the ethereal Nomadland and winning the Academy Award for Best Director in 2021, she was pulled into the vortex of the algorithmic and IP machine, and gave us Eternals, a film everyone would like to forget, from the audience to the studio. Now that she’s escaped again, she’s giving us Hamnet, a movie about grief and art that has premiered at festivals to rapturous reviews and is poised to compete for Oscars.

So, what to do? This essay won’t stop the oligopoly from consuming the storytelling landscape. Neither will antitrust regulators. Show business is a business, and it always will be.

But what we consume does, truly, matter. It’s essential to appeal to the people in our lives, and remind them of the importance of seeking out imaginative work that might stoke the fires of their own creativity.

Because we aren’t just talking about entertainment here, or distraction, or leisure. We’re talking about the narratives that comprise the world we live in. When our imagination narrows, so does civic engagement. The stories that make us confront our reality are the ones that nudge us to change it. If we’re left only with stories that make us comfortably numb to our reality, we invite a world that metastasizes into an intellectual complacency that keeps us stagnant and, in extreme cases, blind.

Sinners became the first movie in over a decade to turn that kind of profit because the creators tapped into something we’re all feeling. The essence of the story is a young boy being pulled in three directions, all of which promise transcendence: his dad’s church, the incredibly seductive vampires with Irish and Southern accents, and music. He chooses music.

It tapped into our collective need for new pathways to transcendence. Because beneath all that doomscrolling, we’re all looking for a way to connect with something deeper. Let’s not ignore that yearning. Start by choosing what moves you, instead of the pull of monolithic institutions and soul sucking feeds. The boy did. So can we. (RR)