Colin Nagy | April 1, 2025

The French Colonial Travel Edition

On Bali, expositions, and early-1930s Paris.

The below is an excerpt from Radit Mahindro’s new book, Paras - Documenting 100 Years of Hospitality and Hotel Architecture in Bali. Radit is a friend, and we’re happy to have this teaser of his exciting new book today.—CJN

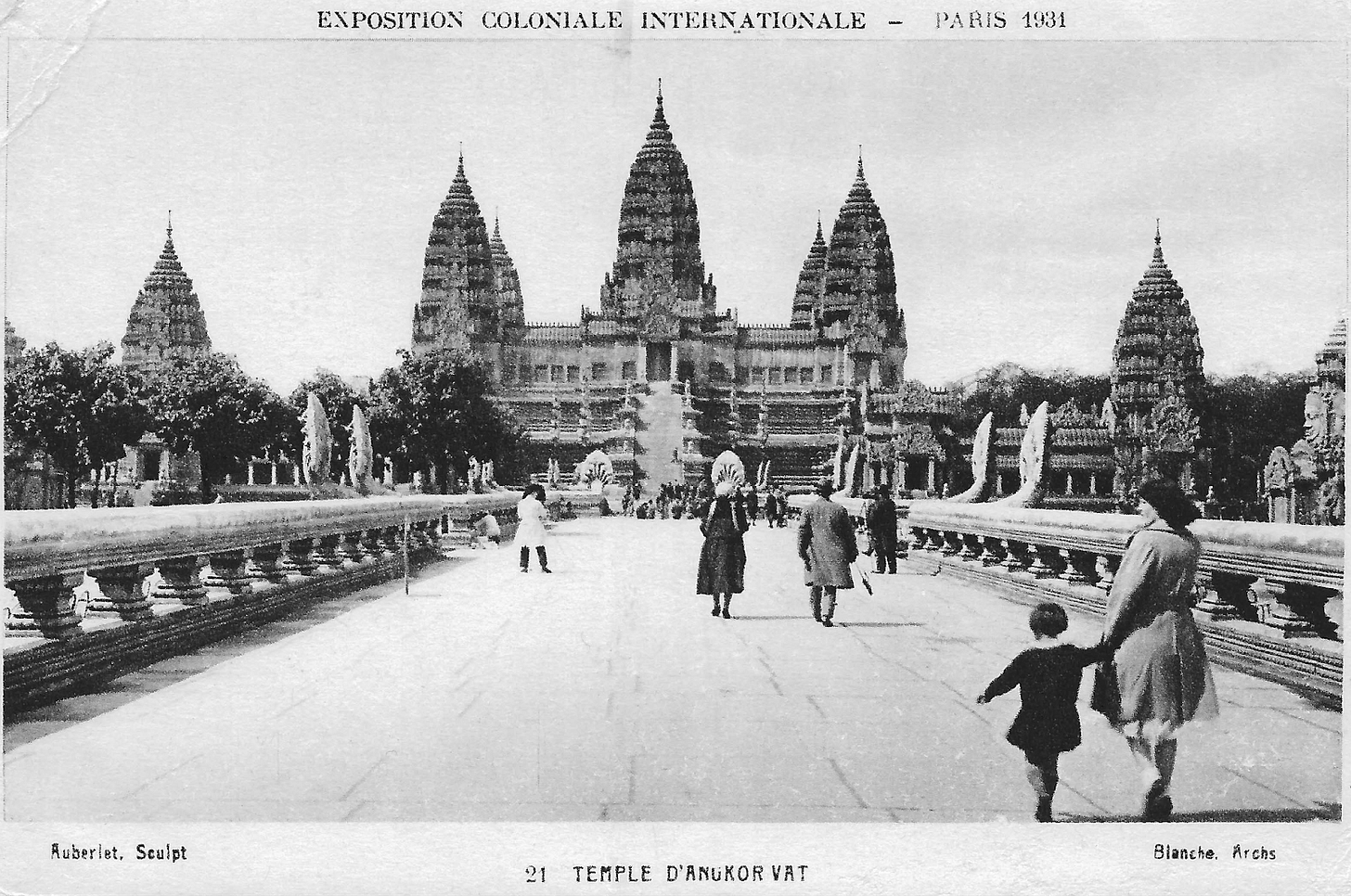

Following World War I, France boasted the world’s largest colonial empire, encompassing 47 nations under its influence. The 1931 Exposition Coloniale Internationale—International Colonial Exhibition—in Paris aimed to unite these diverse peoples in the French capital. The primary goal? To educate and excite the French public about the significance of their colonies. “The exposition will have achieved its goal if, as a result,” then-Minister of the Colonies and future Prime Minister Paul Reynaud said, “many young people develop a desire for a career in the colonies!”

Why is this interesting?

The Exposition also harboured an underlying philosophy – the “mission civilisatrice”, a century-old belief justifying French colonialism. As Le Maréchal Hubert Lyautey, the Exposition’s Commissioner General, put it: colonisation wasn’t just about infrastructure, it was about “instilling a humane gentleness” in the “wild hearts” of the colonised. The exposition, then, aimed to demonstrate the success of this mission, showcasing how colonial industries, though “primitive” when compared to the “civilised” world, were progressing from savagery to civilisation.

The exposition drew a staggering eight million visitors. This logistical marvel required 25 years of planning, over 1,000 days of construction, and the transformation of over 110 hectares in the Bois de Vincennes—including the zoo, a metro line extension, and a redesigned Porte-Dorée station.

However, modern critics have looked back at the Exposition as a “human zoo,” due to the presence of the colonised people brought in to represent their homelands. These individuals lived in constructed pavilions throughout the event, donning traditional attire, selling local crafts during the day, and performing cultural dances during the night for Parisian elites.

Major European powers like Great Britain, Germany, and Spain declined the invitation to join the exposition. Ultimately, only five European states (Denmark, Belgium, Italy, Netherlands, and Portugal) built pavilions alongside France. The United States was the only non-European country exhibiting itself as a colonial power. The American building at the exposition was a replica of George Washington’s house at Mount Vernon, complete with the bedroom set aside for Lafayette.

The Dutch Pavilion, situated in what is now the Paris Zoological Park, drew inspiration from various buildings and monuments across the Indonesian archipelago. Architects P.A.J. Moojen and W.J.G. Zweedijk designed the pavilion in sections, aiming to represent both the grandeur and the artistic heritage of the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia). The main pavilion, with its imposing 110-metre facade, covered a vast area of over 6,000 square metres.

A “Balinese wall” connected the main pavilion to a smaller building housing representatives of Dutch companies. This wall featured a replica of a Candi Bentar, the traditional split gateway of Balinese temples. Entering through this portal, visitors found themselves in a recreated Balinese temple courtyard, complete with altars, towers, and decorated walls – a space dubbed the “Indigenous Square.”

A column by Gérard Houville in Le Figaro captured the pavilion’s mystique: “Bali, the island of Bali, baptised or not by this legendary character, is one of the beautiful possessions of Holland in the great Asian archipelago, and at the Vincennes Exhibition, it built its charming theatre in a place which, in the evening, seems slightly displaced and, under the dim lights, a little mysterious.”

However, the Javanese anti-colonial newspaper Timboel offered a different perspective, criticising the aesthetics: “Who cares? Bourgeois Paris is flabbergasted because it doesn’t know any better!”( They had previously warned against expositions becoming “a parade of eccentricities” that trivialised cultures.)

On the night of June 28th, disaster struck. The Dutch Pavilion burned down while Princess Juliana of the Netherlands was visiting Paris. This accident dominated French newspapers, with photos of the burning pavilion, firefighters battling the blaze, and Princess Juliana at the scene gracing the front pages. The cause of the fire remained undetermined – theories ranged from a short circuit to flammable materials, even arson. The collections lost were irreplaceable. But as the fire did not reach the theatre, the pavilion’s Balinese shows went ahead during the reconstruction work. The number of spectators at the Balinese shows increased considerably after the fire.

The accident generated deep turmoil and compassion in the press, and the rapid reconstruction of the pavilion aroused general admiration. From June to September 1931, a troupe of 51 Balinese performers (14 women and 37 men) captivated audiences at the Dutch Pavilion. Their stay, and the buzz it generated, extended well beyond their scheduled time.

The immense media attention surrounding the Balinese dances propelled Bali onto the international stage. These performances likely sparked awareness about the commercial potential of Balinese art forms, among both locals and foreigners. Just like that, Bali was poised to become a destination for wealthy tourists. (RM)