Colin Nagy | November 12, 2024

The Captagon Edition

On a sanctioned Syria, amphetamine margins, and geopolitical leverage.

Colin here. In modern geopolitics, sanctioned states typically turn to creative—and often shady—means of survival. Iran, hemmed in by economic sanctions, has built a clandestine network of oil smuggling operations, moving its crude oil under the radar to generate revenue. North Korea, isolated by decades of international restrictions, has turned to cybercrime, orchestrating sophisticated hacks that funnel millions back into the state’s coffers. And Syria, heavily sanctioned and economically devastated, has found its lifeline in Captagon, a powerful amphetamine that has swept across the Middle East.

Why is this interesting?

In Syria’s case, Captagon production isn’t just a black-market venture—it’s the backbone of a zombie economy and its profitability means it is one of of Syria’s most valuable exports, outpacing legitimate exports and serving as crucial financial support for a regime battered by years of civil war and sanctions. Rough estimates suggest that Captagon production brings in billions of dollars annually, making the country one of the world’s major producers of amphetamines.

The cross border movement of the stimulant also has consequences for Syria’s neighbors: rising addiction rates in Saudi Arabia, a constant flood of smuggling attempts in Jordan, and heightened border tensions.

The New Yorker recently did a deep dive on the subject, and the economics are fascinating:

In Syria, a single pill of the stimulant costs a few cents to produce. But that pill can be sold elsewhere in the Middle East—the only part of the world where captagon is a popular drug—for as much as twenty-five dollars, especially in wealthy cities such as Riyadh. The margins of the business are high enough that exporters can be unsuccessful as often as not and still reap giant profits. The Assad regime now controls much of the captagon trade, making billions of dollars a year. The most significant figure in the government’s production and distribution of captagon is reportedly the President’s younger brother Maher al-Assad, who is the head of the 4th Division of the Syrian Army, a unit founded in 1984 to protect the government from all threats to its authority. Caroline Rose, who studies the captagon trade at the New Lines Institute, a think tank in Washington, D.C., told me that Syria’s amphetamine business is worth some ten billion dollars. The country’s official gross domestic product is only nine billion.

This, of course, also brings to mind other narco-states in history: Colombia, Bolivia and other Central/South American economies relied on the robust cocaine trade in the 80s, and the Taliban were seed funded (pardon the easy pun) from poppies and the resulting opium production.

The proliferation of Captagon has put strain on the public health and security infrastructure of Syria’s neighbors, straining diplomatic ties and exacerbating regional instability. Saudi Arabia is now seeing a surge in addiction rates, prompting the government to crack down on the drug's entry points and consider social reforms to address the crisis. Jordan has fortified its border with Syria, dealing with near-daily confrontations with smugglers and even deploying airstrikes to curb trafficking.

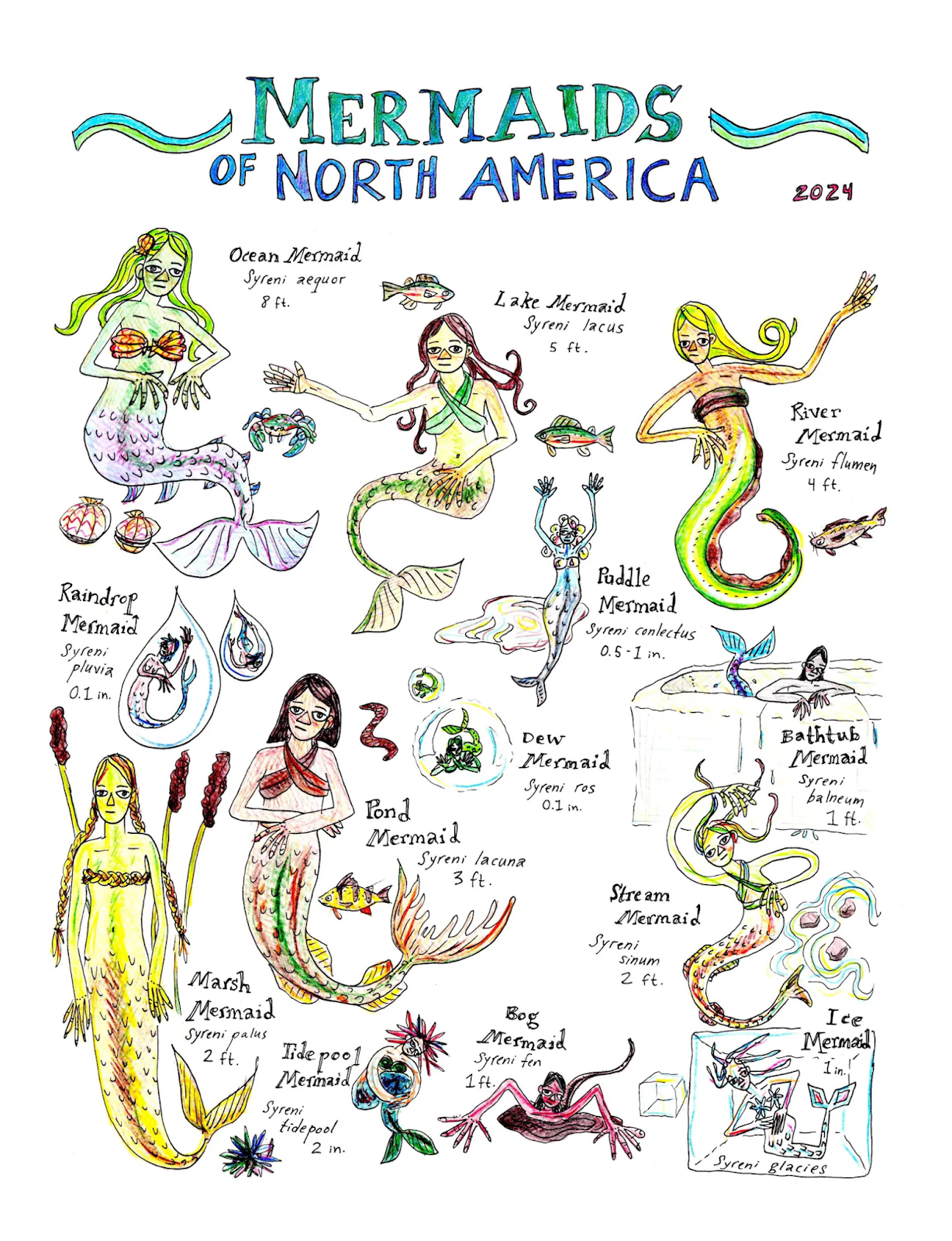

Our friend Edith Zimmerman—an occasional WITI contributor and author/illustrator of the excellent Drawing Links—has started an Etsy store to sell her art. We like promoting our friends, and you should be getting your holiday shopping done early. Shop her full store here.

Tackling the Captagon trade isn’t easy. Any actual progress would require cooperation from the Syrian government, a dictatorship that obviously benefits from the trade and its juicy margin.

However, as Syria needs capital for reconstruction, one could surmise that this could be an ongoing (and effective) tool of leverage in trying to curtail the trade. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are among the few entities with the resources and potential willingness to finance significant reconstruction projects. And it amounts to big business.

In exchange for funding, GCC countries can press for specific anti-trafficking measures, such as dismantling Captagon production sites or taking action against officials known to be involved. An easy solve would be for Assad to direct the margin rich flow elsewhere, which has other terror financing or illicit implications (think Hezbollah, or even as far as Africa or Latin America). So it likely won’t be as easy as turning off the pill factories. And, just like the drug’s ability to hook users, the margins and the personal financial benefit for some of the Assad clan might be hard to extricate from Capagon’s mind altering clutches. (CJN)